Onboard container vessel Tukuma Arctica and for the owner Royal Arctic Line, safety is first and foremost a matter of people taking care of each other on the trips across the North Atlantic between Denmark and Greenland. In addition, it is about ownership and the right level of experience among the crew.

For the crews and employees of the Greenlandic shipping company Royal Arctic Line, harsh and not least extremely cold weather is not exactly an unfamiliar factor to deal with, and it is also a recurring topic when UFDS visits the shipping company's largest container ship, the Tukuma Arctica.

However, this round of the visit takes place in quite calm conditions at the Port of Aarhus, where the almost 180-metre-long vessel, which can take 2148 TEU fully loaded, is bunkering. Tukuma sails in a fairly fixed pattern between Nuuk and Aarhus, with stops in Iceland and the Faroe Islands along the way, in addition to Helsingborg.

With just over three years at sea since she was built at a shipyard in Guangzhou, China, Tukuma Arctica is among the newest ships in Royal Arctic Line's fleet of 12 vessels. Of these, 11 are freighters, while the last, Sarfaq Ittuk, takes passengers and cruise tourists up and down the Greenlandic coasts.

On board Tukuma, master Jacob Meyer Skou greets and shows around the vessel, which he himself helped bring home from China in 2020, then as chief mate. For him, safety is something that must be incorporated into everything the 18-man crew does on the ship.

»Safety just means a lot at sea because we are so far away from being able to get help when we´re in voyage. So, if one of us is injured, we must be able to patch them up ourselves and handle documentation, sick leave and whatever further consequences may arise,« he says.

The basic idea is therefore, quite simply, that people should at least be able to travel home in the same condition as they left, 'and preferably better and wiser', as Jacob Meyer Skou says with a smile.

»It basically requires us to take care of ourselves and each other, so we strive for that every day. To that end we have the usual requirements to protect ourselves with work clothes, safety shoes, helmets and other equipment, and also that you think twice and don’t climb up a mast in the middle of a storm,« the skipper says.

Likewise, it is important not to take on something risky without informing at least one colleague about it, and that you make sure to do things by the book with, for example, fall belts when working aloft.

»We can't have people thinking that they just need to fix some valve that is in some totally impassable place, and then they go ahead without telling anyone, and then if they fall or get stuck, nobody knows where they are,« Jacob Meyer Skou says.

All eyes must be included

A veteran of almost 17 years in Maersk, many of which as chief mate on the enormous Triple E vessels, Jacob Meyer Skou knows what it means to be part of a vast organization. Against this background, he greatly appreciates his move to Royal Arctic Line in 2018, which – all other things being equal – is a somewhat smaller business, despite more than 700 employees.

»I've been super happy to come here, it's really a great place to be. Everyone can talk to each other, there is a fairly flat structure, you know your colleagues on land and are on a first-name basis with most people. I really like that,« he says.

In terms of safety, it also makes a difference, he believes, because RAL is very much committed to ensuring that each seafarer takes ownership of his or her tasks. The crew members are typically assigned to the same ship for longer periods, preferably two to four years, and in the master's view, this results in a more pronounced sense of responsibility.

»It means that people know that if they mess it up, you have to take care of it, because you meet the same colleagues again six weeks later. People are held accountable, and then they take this ownership. We feel that it is our own ship, and then you go that extra mile to make sure that it is a nice and safe place to be,« Jacob Meyer Skou says.

Specifically, he gathers his people on the bridge for a catch-up meeting every time a six-week tour is coming to an end, to talk about how things have gone or if anyone has anything to say. If there has been an incident, you can talk it through and, in general, everyone gets the opportunity to have their say.

At the meetings, the master makes a virtue of an open dialogue, where both ship assistants, engineers and officers can talk on an equal footing, and everyone can report if they have seen something that requires action. Because as the master says, 'If all eyes are with us, we can catch most things.'

»If you see something, say it and then we can fix it. This doesn’t mean that you have to fix it yourself. Sure, if it's something simple, go ahead, but if it's something more complicated, get a marine engineer to look at it. So, we encourage everyone to join in,« Jacob Meyer Skou says.

Have seen all the teething problems

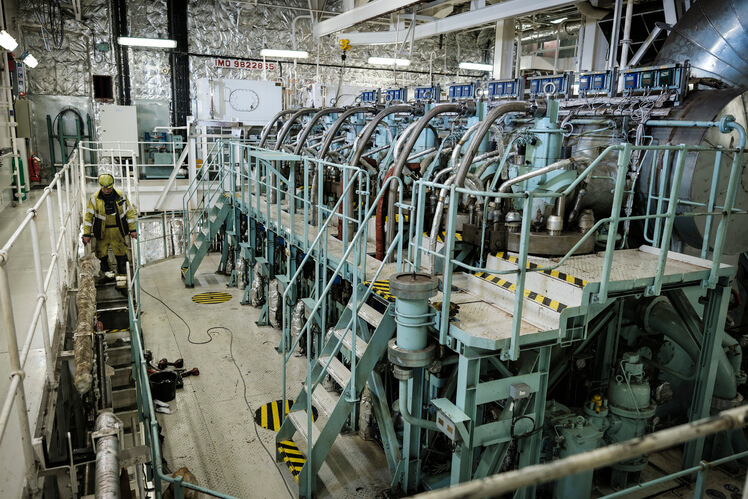

As mentioned, Jacob Meyer Skou has been at Tukuma Arctica since day one from when Royal Arctic Line put her into use in 2020, and the same applies to Chief Mate Rasmus Bundgaard Hansen. It is important in a safety context, he stresses, to have people on board who are familiar with the history of a vessel.

»We've seen all the teething problems and all the small and big issues with things that have broken. With a new crew member, it can take several days to bring them up to speed, so you save a lot of time by having the experience on board,« he says.

In the same breath, however, he emphasizes the build in balancing act, because of the regular – and necessary – continuous crew turnover on the ships, requiring a certain flow of cadets in training on board.

This is also the case at Tukuma, where trainees in the engine or on the bridge are a regular feature, making sure that they are familiarized with the ship's safety systems, procedures and equipment along the way.

This applies, for example, to the two stations with smoke diving equipment on board, located at opposite ends of the ship, so you can (hopefully) always get to at least one of them in case of fire. Each station houses two smoke diving suits, complete with a new type of helmet with built-in Bluetooth communication, so the two smoke divers can talk directly and hands-free to each other.

To ensure that the equipment works and that the crew is familiar with its use, fire drills are held on board at least once a month. These also include some of the equipment from the ship's hospital, which is quite well equipped with stretchers, medicine, and a bathtub for rinsing or thermal treatment.

»One of the things we really respect is if someone has a fall deep in the engine or inside a ballast tank or somewhere else that's hard to get to, so we have some special equipment for that, and we train with it too, so people know what's going to happen,« Jacob Meyer Skou says.

On a day-to-day basis, it is the chief mate who acts as the ship's medical therapist with responsibility for ordering supplies to the hospital and taking care of minor injuries, just as he handles the dialogue with Radio Medical, where you can get in touch with Danish doctors around the clock in case of need for help with a diagnosis or permission to administer, for example, morphine.

Pros and cons of large windows

In the ship's mass, Jacob Meyer Skou explains how, since the commissioning of Tukuma Arctica, parts of the furniture have been or is due to be upgraded – better chairs, beds, sofas and the like – just as the working environment in several of the common areas has been improved by installing acoustic panels in the ceilings.

»In the past, the acoustics in here were so poor that you basically couldn't have a normal conversation if we were sailing at full throttle, and that's obviously no good in a room where you stay for long periods of time. But these plates stifle that reverb, so now it's like a normal living room,« he says.

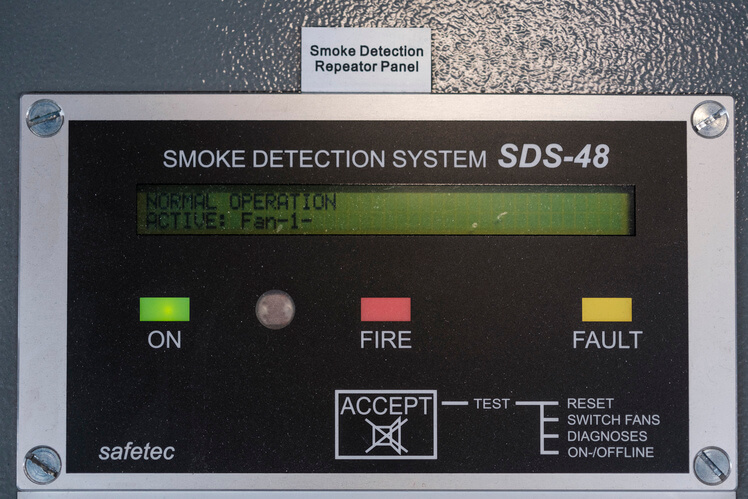

Fire extinguishers and alarms are all over the place, and the galley feaures independent systems over, for example, the fryer, in addition to of course first aid equipment, eye wash kits and the like.

Tukuma is also well-equipped when it comes to the mandatory life rafts, man-overboard boat, and whatever else belongs on the deck of an ocean-going container ship. This includes, among other things, a solid overcapacity in the number of seats in the boats, making sure everyone can get offboard in case of an accident.

During a pit stop in his own cabin – of course the ship's largest sporting a separate bedroom – Jacob Meyer Skou shows the small collection of phones available to him, including an internal emergency phone with manual charging, a normal internal phone and a satellite phone, in addition to his cell.

Up on the bridge, the master highlights the extended windows stretching almost to the floor and thus providing an excellent horizontal view and, not least, a sharp angle downwards when Tukuma has to navigate icy waters in Greenland.

However, the large glass surfaces present some challenges in relation to keeping a proper temperature during the colder parts of the year, and for that matter also in the summer, when the indoor climate tends to lean towards a greenhouse-y feel.

In addition to the visit in the Port of Aarhus, UFDS has also visited Tukuma Arctica in Nuuk, while the container cranes were running in the early morning during a snowstorm no less. You can read more about the visit here.